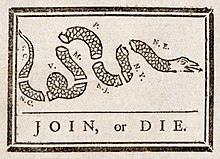

Join, or Die

Join, or Die. is a political cartoon showing the disunity in the American colonies, originally in the context of the French and Indian War in 1754. Attributed to Benjamin Franklin, the original publication by The Pennsylvania Gazette on May 9, 1754,[1] is the earliest known pictorial representation of colonial union produced by an American colonist in Colonial America.[2] It was based on a superstition that if a snake was cut in pieces and the pieces were put together before sunset, the snake would return to life.

The cartoon is a woodcut showing a snake cut into eighths, with each segment labeled with the initials of one of the American colonies or regions. New England was represented as one segment, rather than the four colonies it was at that time. Delaware was not listed separately as it was part of Pennsylvania. Georgia, however, was omitted completely. As a result, it has eight segments of a snake rather than the traditional 13 colonies.[3] The poster focused solely on the colonies that claimed shared identities as Americans. The cartoon appeared along with Franklin's editorial about the "disunited state" of the colonies and helped make his point about the importance of colonial unity. It later became a symbol of colonial freedom during the American Revolutionary War.

History

[edit]Seven Years' War

[edit]The French and Indian War was a part of the Seven Years' War which pitted Great Britain alongside the Thirteen Colonies and their native allies against the French, New France and their native allies. Many American colonists wished to gain control over the lands west of the Appalachian Mountains and settle there (or make profits from speculating on new settlements). During the outbreak of the war, the American colonists were divided on whether or not to take the risk of actually fighting the French for control of the lands west of the Appalachian Mountains. The poster quickly became a symbol for the need of organized action against the threat posed by the French and their native allies during the conflict, as while many Americans were unwilling to participate in combat against the French, many more recognized that if the French colonies were not captured they would always pose a risk to the well-being and security of the Thirteen Colonies. Writer Philip Davidson stated that Franklin was a propagandist influential in seeing the potential in political cartoons to stir up public opinion in favor of a certain way of thinking.[4] Franklin had proposed the Albany Plan and his cartoon suggested that such a union was necessary to avoid each colony being captured individually by the French. As Franklin wrote:

The Confidence of the French in this Undertaking seems well-grounded on the present disunited state of the British Colonies, and the extreme difficulty of bringing so many different Governments and Assemblies to agree in any speedy and effectual Measures for our common defense and Security; while our Enemies have the very great Advantage of being under one. Direction, with one Council, and one Purse. ...[5]

American Revolution

[edit]

Franklin's political cartoon took on a different meaning during the lead up to the American Revolution, especially around 1765–1766, during the Stamp Act Congress. American colonists protesting against the rule of the Crown used the cartoon in The Constitutional Courant to help persuade their fellow colonists to rise up. However, the Patriots, who associated the image with eternity, vigilance, and prudence, were not the only ones who saw a new interpretation of the cartoon. The Loyalists saw the cartoon with more biblical traditions, such as those of guile, deceit, and treachery.[6] Franklin himself opposed the use of his cartoon at this time, but instead advocated a moderate political policy; in 1766, he published a new cartoon MAGNA Britannia: her Colonies REDUCED,[7] where he warned against the danger of Britain losing her American colonies by means of the image of a female figure (Britannia) with her limbs cut off. Because of Franklin's initial cartoon, however, the Courant was thought of in England as one of the most radical publications.[4]

The difference between the use of Join or Die in 1754 and 1765 is that Franklin had designed it to unite the colonies for 'management of Indian relations' and defense against France, but in 1765 American colonists used it to urge colonial unity in favor of resisting laws and edicts that were imposed upon them. Also during this time the phrase "join, or die" changed to "unite, or die," in some states such as New York and Pennsylvania.

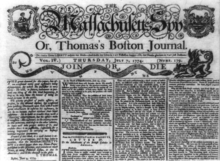

Soon after the publication of the cartoon during the Stamp Act Congress, variations were printed in New York, Massachusetts, and a couple of months later in Virginia and South Carolina. In New York and Pennsylvania, the cartoon continued to be published week after week for over a year.[4] On July 7, 1774 Paul Revere altered the cartoon to fit the masthead of the Massachusetts Spy.[8]

Legacy

[edit]The cartoon has been reprinted and redrawn widely throughout American history. Variants of the cartoon have different texts, and differently labeled segments, depending on the political bodies being appealed to. During the American Revolutionary War, the image became a potent symbol of the unity displayed by the American colonists and resistance to Parliament and The Crown. In the 19th century, it was redrawn and used by both the Union and Confederacy during the American Civil War.[9]

President-elect Donald Trump's pick for Secretary of Defense, Pete Hegseth has the cartoon tattooed on his right forearm.[10]

See also

[edit]- Gadsden Flag

- Live Free or Die

- United we stand, divided we fall

- The American Rattle Snake, another cartoon featuring a rattlesnake

References

[edit]- ^ "Join, or Die". Pennsylvania Gazette. Philadelphia. May 9, 1754. p. 2. Retrieved January 19, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Margolin, Victor (1988). "Rebellion, Reform, and Revolution: American Graphic Design for Social Change". Design Issues. 5 (1): 59–70. doi:10.2307/1511561. JSTOR 1511561.

- ^ "Join or Die Snake Historical Flag". Flags Unlimited. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ^ a b c Olson, Lester C. (2004). Benjamin Franklin's George Washington Vision of American Community. Columbia, S.C: University of South Carolina Press. hdl:2027/heb09323.0001.001. ISBN 978-1570035258. LCCN 2003021485.

- ^ "The Writings of Benjamin Franklin: Philadelphia, 1726–1757". historycarper.com. Archived from the original on May 12, 2006. Retrieved May 1, 2006.

- ^ Stone, Daniel P. (January 10, 2018). "JOIN, OR DIE: Political and Religious Controversy Over Franklin's Snake Cartoon". Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved August 3, 2023.

- ^ "Political cartoon: MAGNA Britannia: her Colonies REDUC'D". Library Company of Philadelphia. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- ^ "A More Perfect Union: Symbolizing the National Union of States". Library of Congress. July 23, 2010. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ^ "'Join, or Die' – the Political Cartoon by Benjamin Franklin". BBC. 2003. Retrieved December 13, 2006.

- ^ Haley Gunn. "Trump's Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth's Tattoos Decoded as Pentagon Slams Don's Selection of Fox News Host for Key Position". Radar. Retrieved November 15, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Copeland, David. (1998). ""Join, or die': America's press during the French and Indian War-". Journalism History. 24 (3): 112–23 – via ProQuest.

- Olson, Lester C. (February 2, 1987). "Benjamin Franklin's pictorial representations of the British colonies in America: A study in rhetorical iconology". Quarterly Journal of Speech. 73 (1). Informa UK Limited: 18–42. doi:10.1080/00335638709383792. ISSN 0033-5630.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- American Revolution

- Editorial cartoons

- American political satire

- Satirical cartoons

- Works about the French and Indian War

- Mottos

- National symbols of the United States

- Works by Benjamin Franklin

- 1754 works

- Propaganda cartoons

- Woodcuts

- Snakes in art

- 1754 in politics

- 1754 in the Thirteen Colonies

- 18th-century prints

- 1750s neologisms

- 1750s quotations